If you’ve studied the art and science of tracking, you’re aware of how effective it can be in a combat environment. Specifically, in this instance we’re talking about the actual the cutting of sign and running bad guys into the ground or killing them, vs. how effective tracking is at training situational awareness. Several modern militaries (in this case, we’ll define “modern” as post-WWII) have historically employed trackers more effectively and consistently than others.

Among the very best of those were the Rhodesians. Students of tracking (and irregular or counterinsurgency warfare in general) will recognize names like Selous Scouts, Tracker Combat Unit, Gray’s Scouts, C Squadron SAS, RLI/RAR, and others. Usually, even those who’ve studied the Rhodesian Bush War think of those trackers as older, seasoned soldiers or SOF troops.

However, the ability to track was far more endemic to the Rhodesians than that.

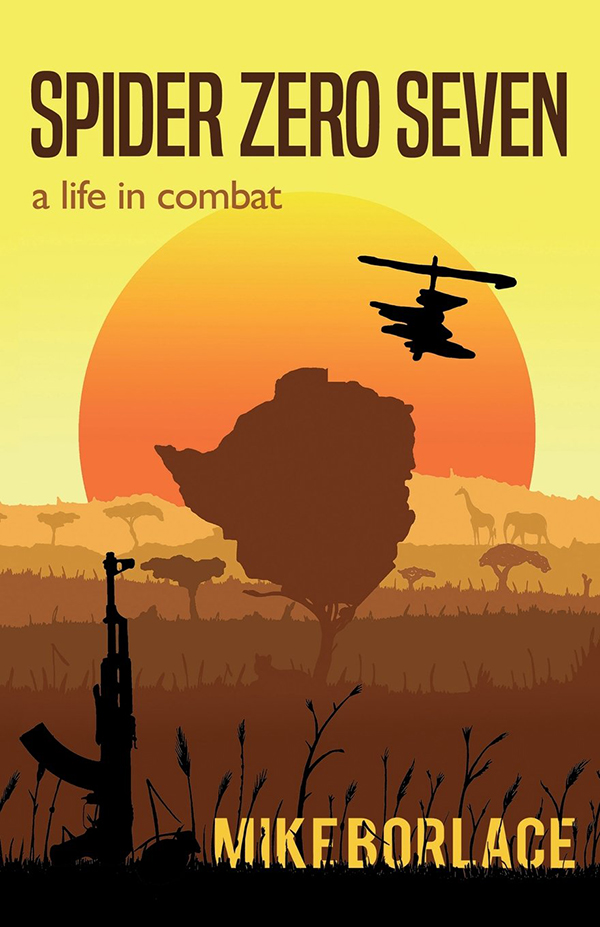

The following is an excerpt from the memoirs of decorated Rhodesian helicopter pilot Mike Borlace.

There are a number of interesting lessons to be drawn from it. This probably took place in mid- to late-1975 after the coup in Portugal that led to the independence of several Portuguese colonies, including Mocambique. This opened a couple of thousand miles of Rhodesian border to terrorist attacks.

A farm has been attacked just before dawn in a remote area about fifteen clicks on our side of the border. The farmer and his wife have returned fire and driven the attackers off, and by chance there was a tracker team at a police post in the vicinity who are already on tracks heading through the forest towards the border.

We have a G-Car1 but no troops available, the rest of the fireforce having gone up to Umtali to support some operation and ending staying overnight, so I get airborne with the territorial army major and Brian Booth as the gunner. Brian is one of the new gunners on the squadron, about eighteen years old and known as Basil Brush due to his uncanny resemblance to the popular ventriloquist’s dummy.

We arrive overhead of the trackers, who can’t be seen due to the dense pine forest they are working through. We establish their position by getting them to read us overhead and take their sitrep – they reckon they are close up on tracks of two and about half an hour behind. We brief them that we will fly ahead along the line of flight of the gooks which will hopefully slow them down, and that if they make contact to throw a white phos. We’ll then shoot through the trees in the area ahead of them on the far side of the white smoke, which will keep the gooks from running too far ahead.

![]()

Every ten minutes or so, the tracker stick reads us back overhead so we are up to date with their progress and their sitreps indicate that they are closing on the two fleeing insurgents.

Finally, there is a whispered, “We have two CTs visual.”

“Well done.”

This team has performed really well and caught up with the gooks about two hours after starting. There is a pause of about a minute before they come back on the air.

“What shall we do?”

“How far away are they?”

“About twenty-five yards.”

The major and I look at each other a little perplexed.

“What are these guys doing? Do they know you are there?”

“They’re resting. No, they have no idea we are here.”

That explains the whispering. The army officer and I exchange puzzled looks again. What is going on here? With the fireforce we normally get informed after the initial contact has taken place.

“Is there some problem? Can you not get a clear shot at them?”

“Negative. I’ve got one in my sights now, and the other one is covered with the MAG.”

Jesus, what are they waiting for? “Is there some reason you can’t open fire?”

“Negative. Can I open fire?”

Good God!

“For Christ’s sake, shoot!”

We wait for a couple of minutes – the last thing you need in the middle of a punch-up2 is somebody calling you on the radio – and then ask how things are going.

A bit breathless now, “OK. OK. Contact is over, we’ve got two dead CTs, no casualties to us.”

We congratulate the callsign; they really have done very well to catch up and make contact so quickly. We give them directions towards a logging track and tell them that we’ll make arrangements for the police to pick them and the bodies up on that road, and that we’ll see them later.

We don’t in fact meet this stick until the following day, and then the reason for the delay in initiating the contact becomes apparent. The stick leader is an eighteen-year-old, and the other three are seventeen, all doing their national service. They have recently been schoolboys and, of course, have spent their lives learning that you don’t gratuitously kill things, let alone people.

Slightly deeper analysis starts you wondering as to the ready acceptance of an authorisation from a disembodied voice over the radio, but anyway, the aggression and tracking skill shown by these school kids has really impressed me.

*

Interested in more? Read Bush tracking and warfare in late twentieth-century east and southern Africa.

Learn to track: Weaponize the Senses is situational awareness training.

1 A G-Car was a helicopter gunship used in support of Rhodesian security forces operation. A K-Car was a command helo. The Rhodesians primarily used the Alouette III in fireforce operations.

2Punchup – similar to a dustup or brouhaha, a firefight.